This week, I was back in south Florida, and I was relieved to find that (at least the area I was in) was pretty much back to normal. There were a few billboards whose advertisements were ripped by the wind, and a few palm trees with lost fronds, but for the most part, everything had already been cleaned up, and I didn’t encounter any sort of power/water issues. I was so glad to see my client’s area back to normal! However, I know there are still a lot of islands in the Caribbean with horrible devastation – I hope all the hurricanes ease up and give them the opportunity to recover and rebuild 🙁

On this Travel Thursday, I wanted to discuss some misconceptions I’ve heard about the airline industry with response to the hurricanes. Namely: there were a lot of media outlets falsely reporting that airlines were jacking up prices in order to profit from the storm. The more I read, the more I realized that so many people still have no idea how airline pricing works.

Here’s a quick primer on airline revenue management. In a nutshell, an airline’s pricing department sets the price points and rules for each fare class on a specific route. So, a Y-class fare might be selling for $2000, an O-class fare might be selling for $50, and then you’ll have a whole lot of price points in between. What price does that mean you pay? That’s decided by the rules of the fare class (e.g., some may be valid only on certain days of week or certain routings), and how many seats have already been sold on the plane. It’s that last piece that’s critical to understanding the high-priced hurricane flight debacle.

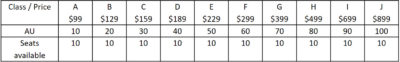

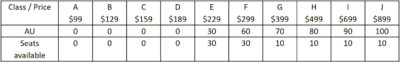

Fare classes are nested one inside the other, so when one fare class sells out, the system will automatically start selling the next class above it. Take a look at this example of a 100-seat plane with no overbooking that has step-wise allocations (AUs) of 10 seats per class:

The first 10 seats for sale on that flight will be sold in A class, at which point that class will “close” and B class will begin selling. Once 20 seats sell (the first 10 in A, the next 10 in B), C class will begin selling. So if the AUs remain unchanged, the earlier you book, the better the price you will get. And if you are one of the last ten people to book, you’ll be paying a whopping $899 for a ticket that only cost the first ten people $99.

If the above protections were how an airline had allocated their seats, you’d find that with only one or two seats left on any flights out of Florida, there would be no tickets priced less than $899. What might seem like price gouging would be a simple case of the system doing its job. As more and more people booked seats, the airlines themselves weren’t increasing flight prices, but the planes were getting so full that the system was automatically charging top dollar for those last few seats on each flight. Most of the time, you won’t see those expensive fares truly being sold – but when everyone is trying to get out before an emergency, there’s no supply of seats and so the few seats left are automatically priced exorbitantly high.

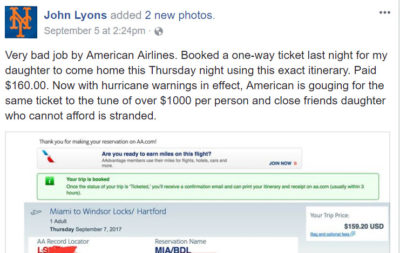

In order for prices to not be sky-high in light of such demand, airlines would have to manually intervene… and that’s exactly what most did. JetBlue and American Airlines, for example, eventually capped the price of one-way flights out of Florida at $99. A benevolent move, for sure – or at least that’s my opinion, though airline-haters would say it was only in response to bad publicity.

But this kind of help during the storm wasn’t unprecedented for the travel industry: Southwest sent planes to Puerto Rico to rescue evacuees from other islands who were stranded there. (And I’d like to remind people that with planes being so expensive, no airline has tons of extras just sitting around – these were most likely pulled out of profitable service somewhere else.) And Norwegian Cruise Lines allowed passengers who lived in Florida to stay on board their ship and wait the storm out somewhere else (even though NCL themselves didn’t yet know where). People love to hate the travel industry, but it is about providing hospitality, and I’m proud that so many companies tried to help however they could.

But should price gouging be illegal? It’s a very negative term, but it’s actually not an entirely bad thing. An opinion piece on Slate talks about how price gouging bans can make disasters even worse. Price gouging creates incentives for people to think harder about what they truly need, and also rewards vendors who manage their inventories well and can provide that supply at critical times. Another article from Forbes posited that there are three options when supply is less than demand: do nothing and allow the supply to run out, raise prices to slow down demand (especially from those hoarding supply), or raise prices to provide an incentive for more supplies to flow into the region.

In the case of the airlines, artificially dropping the prices (as JetBlue and American chose to do) meant that the flights sold out nearly instantly – it was the gasoline equivalent of doing nothing and quickly running out of fuel because whoever happened to show up first immediately bought. Allowing the fare classes to close and the prices to rise accordingly likely would have slowed demand somewhat (as higher prices would have encouraged people to find alternatives to flying), but it also might have encouraged more airlines to send extra planes into the region to get evacuees out. American and United both added dozens more flights out of Miami, allowing thousands more people to evacuate. Would they have sent more planes if the potential revenue was higher? Quite possibly.

And while JetBlue and American capped their one-ways out of Florida at $99, Delta capped theirs at $399. Where do you draw the line for what’s a “fair” price? Before you shame Delta for the higher price: remember, as Hurricane Irma rolled into Puerto Rico, Delta heroically sent in a nearly-empty plane to make a quick turn and bring as many people out of San Juan as possible. It’s not as simple as one airline being good and another being evil.

Like it or not, airlines are businesses who are bound to drive revenue for their shareholders. There’s only so much of a revenue hit an airline can afford to take when it’s already operating under razor-thin margins, and a bankrupt airline is no good to anyone (unless you’re Alitalia and you keep getting bailed out). But in a time of crisis, it’s up to all of us to pitch in and help our fellow humans. In my opinion, airline leadership may not be perfect, but they’re doing the best they can to help with the resources they have. Let’s cut them some slack.